Webhook Design Patterns

Webhooks are lovely little blobs of joy and provide most probably the simplest form of integration for developers and system architects. Yes, they’re just HTTP POST requests, but try and not let their simplicity them fool you. Handling HTTP is an expected capability in every modern programming language, and they can be handled without importing an external library. Every automation system out there is almost guaranteed to support them, and they can be a solid foundation for building systems that deliver high utility.

Popular upstream providers that send webhooks can be transactional email, SMS providers, payment gateways and so on.

For the purposes of this article, I want to describe the upstream system as the one that sends the webhooks and the downstream system as the one receiving them.

Validation

Given today’s application delivery, often from other public cloud platforms, the old days of applying an IP address-based whitelist is dead. The system that delivers webhooks could be on spot instances or containers and how those network architectures look is anyone’s guess. It’s expected therefore that webhooks are cryptographically signed (no, I’m not spouting web3 nonsense), in which a private key has signed a payload and your system using a public key can validate the signature. This is normally done using public key infrastructure (PKI) and it means that a trusted party has signed a certificate to increase the trust level.

Some webhooks send their signature in a HTTP header, others send them as part of a payload, such as in a JSON Web Token (JWT) which includes the signature and a claim.

If you can validate the payload, then you in theory can trust the publisher, providing their infrastructure has not been compromised. Great! But what’s signed and how do you structure the payload?

Systems that create webhooks, will often expose a public certificate for you to use when validating messages. It might be worth storing that in a configuration file, but it adds overhead. A common practice is to obtain the certificate at run time. That way, it’s in memory and a service restart will reacquire the certificate if the key has been swapped.

Payload Structures

Payloads tend to be either arbitrary JSON or in the form of JWTs. Some have useful fields that can tie together upstream and downstream data like a payment notification to a customer account.

Arbitrary JSON will give the implementer the most flexibility but will make your life a nightmare if you’re building integrations against it. Systems that can offer a JSON Schema are helpful to alleviate some of the problem that exists in passing seemingly random JSON between systems. JWTs on the other hand are a standard and must include certain fields. This standardisation provides some needed structure between your system and your upstream service provider. That includes detecting data validity (through expiration and valid-from logic). Custom data is included in the payload part of the JWT which is used to project meaningful data between systems that gains the ability automagically to be valid in a specific time window and furthermore, to be validated easily. They are commonly used in web front-end systems and if you’ve used Auth0 or KeyCloak, then the chances are you’ve consumed them before.

Plain ol’ JSON isn’t bad, but you are at the behest of the upstream developer and the documentation entirely.

Reponses & Retry

Webhooks are transmitted from a system that is informing another system of a meaningful event, most likely if you’re reading this, your system. One way is however a high-level description. A webhook is a HTTP POST verb over TCP, meaning that a simple response is required in the from of a HTTP response code. Some webhook systems are strict and require a 200 response and some are more lenient requiring something in the 2xx series, so a 202 would be acceptable. If 4xx or 5xx responses are sent, then it normally triggers a retry mechanism

Most webhook systems will have a retry system, in which the message is sent multiple times with a backoff time in between each attempt. It’s quite typical for this to be three attempts (the IT world is full of threes!).

This retry and response logic means you have some level of semantic control of the behaviour. If you send a 4xx or 5xx, you will probably invoke a failure log statement on the upstream service in addition to the retry mechanism, but it’s important to know that if the receiver is in maintenance mode or it cannnot access a database, having the option to trigger a retry is a useful thing.

Payload Validation

Knowing that a payload is signed means you can verify who the contents are from, but what about the usefulness of the actual contents?

Unless you’re dealing with something like a new user signing up, some basic state must shared between the upstream and downstream system. This is to coordinate key information on events. The event could be a payment notification on a user registered on your system and to handle it properly, you will need enough user identity information stored locally.

Handling Errors & State Miss Hits

Handling errors on loosely coupled systems driven by webhooks requires some thought. Earlier on in this article, the consequences of sending 4xx and 5xx response codes was mentioned. Is the error an operational one that requires the upstream system to respond appropriately? Or is the error something that can be silently dismissed by sending a 2xx code as a response? In some cases, local logging will be your friend instead of upsetting an upstream system.

What happens if the upstream system fails or badly behaves? Offensive and defensive architecture is key and thinking in terms of “more than once” delivery as part of your design will help solve for this. What will happen to a downstream system if the same message is received by it more than once? Downstream systems should be either idempotent or resistant to triggering the handling process on the reception of multiple identical messages.

Webhook Proxy or Direct Coupling

Webhooks can either be sent directly to a downstream system, or sent to a proxy system which acts like an external middleware. If the upstream system directly sends to the downstream system, then it’s ideal if the upstream system can have selective delivery of webhooks and for more than one destination. Stripe is a great example of that. You can send different webhooks to a development environment vs a production one, or send the same set to both. It’s all your choice. Simple systems may only be capable of sending webhooks to a single downstream system and your choice between development and production might seem like a problem, in which case, webhook proxies to the rescue!

A webhook proxy can be thought of like a store and forward system, but for webhooks. An upstream system will be configured to send their webhooks to a middleware system, like https://webhook.site and then it’s down to the integration engineer to figure out what to do, whether just forward it, or do some local processing first. This pattern is great, because it also means you can work with both production and development environments without disrupting the upstream system. Even better, they can offer a temporal cache, which is great for debugging issues and can run localised processing contained in scripts prior to forwarding anything on. In its most simple form, this can be described as webhook automation and is very powerful. This approach enables use cases like draining nodes from production maintenance windows, or A/B and Canary testing etc.

Webhook automation can be provided in the downstream system’s code base, as well as via an automation platform that happens to have appropriate capabilities. It’s down to personal choice and where you want to maintain complexity.

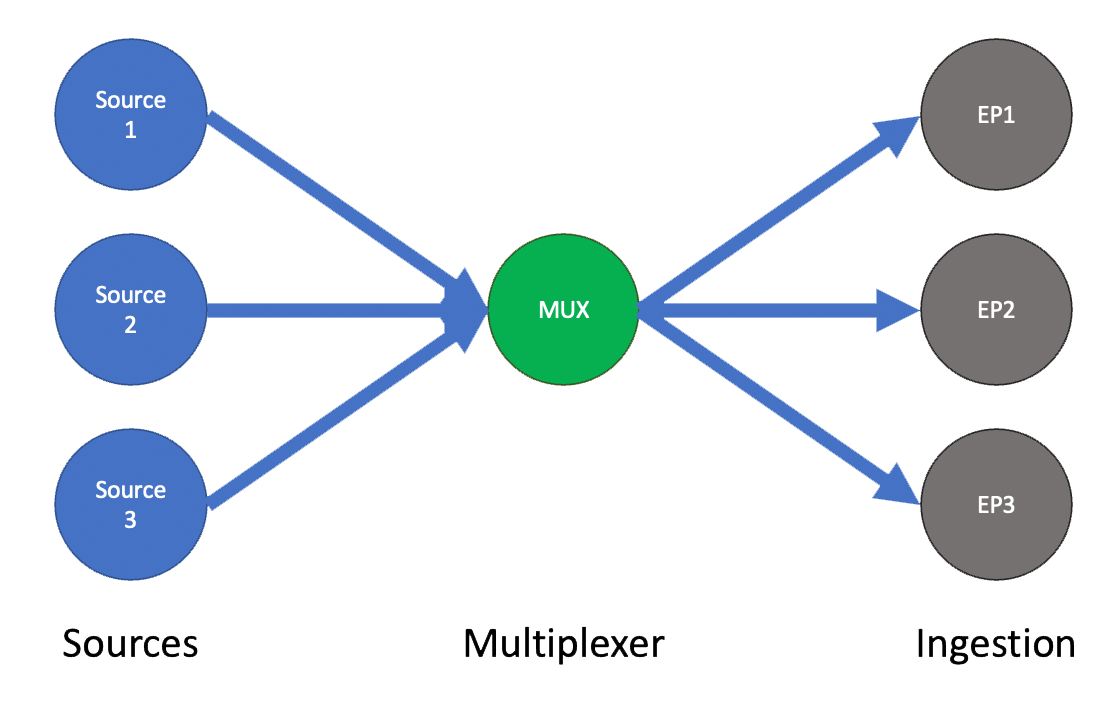

Fan-In

When you consume multiple upstream services, we can refer to it as fan-in. When building an API, it’s normal to have an endpoint for each webhook origin. That would be, one API endpoint for payment notifications, one for email delivery notifications and another for new users joining the system. You could further granularize that by having one specific endpoint for payment success and payment failure if the upstream system has those specific atomic capabilities.

When working with webhook proxy systems, each origin or type within an origin will have its own URL and thus you will have an ordered cache with stored webhooks and specific forwarding actions and rules on that cache. They’re really powerful systems.

Whether you opt for dealing with fan-in in your code base or externally, proper discrimination between different webhook origins and types from those origins, will help keep your code clean and make it clearer for anyone building functionality or maintaining the code.

Fan-Out

This is specific to webhook proxy middleware, but now that you have the webhooks payloads, what are you going to do with them? You might have some aggregation functionality or state machine logic which deals with a set or expected set of webhooks prior to sending a computed payload to a downstream system. A bit like ‘just-in-time manufacturing’, the equivalent would be building an engine prior to installing it in a car. Can you imagine the carnage of building an engine in the car bay bolt by bolt? Some systems offer rich capabilities and they’re to be taken advantage of to give you the ‘engine to car’ behaviour.

The fan-out capabilities of a system aren’t just replicated webhooks with different endpoints but are a rich set of capabilities that can extract, enrich and build new data structures to suit your use case. Some fan-out systems will even offer different upstream capabilities, like direct interaction with other systems like Kafka, AWS SQS and NATS.

Unsolicited Events

What happens if a downstream system receives a message that is cryptographically correct, but has no relatable information? It’s good to perhaps designate response codes for silently accepting information like 200 for success and a 202 for “ok, but I won’t do anything with this”. If you document it, developers will be able to go through logs in upstream systems and see how relevant their coupling is. Also, with a 2xx series response, retry logic will be avoided, keeping chatter to a minimum.

State-Machine Handling

State-machines have been mentioned multiple times in this article, but what can we do with them? Imagine a payment provider sending you multiple but related events.

- Payment charge succeeded

- Payment invoice setup

- Payment invoice complete

- Pro-rata processing (because the user changed plan)

Now, let’s say the downstream system is interested in:

- The charged amount

- The current plan

- Meta data for the plan

- The success of the payment

- The billing period (from, to)

- The URI of the receipt

A set of webhook processing middleware that can combine the payloads and deliver one unified and highly contextual payload is of high value. Automation systems can offload some of the fiddly complexities in asynchronous processing and I hold high the opinion that external systems can assemble meaningful information if done correctly. It keeps the core business logic clean and the problem of assembling and triaging disparate blobs of information to somewhere that is better suited to it. There is always the traditional set of problems to deal with like short term caching and how to deal with ‘data assembly’ errors, but the buck as they say, has to stop somewhere.

Summary

Webhooks are incredibly powerful and I’ve wrote about them in different places. This article completes some of the thoughts I’ve had on them and I hope it’s of value!

Other links maybe worth a read:

Automation platforms that easily handle webhooks:

Webhook Proxy / Middleware:

// Dave

- Tags: webhook, webhooks, loose coupling

- Categories: webhook, webhooks, loose coupling