Learning Vectors: Automation

Info! This article is focussed on thoughts derived from learning software skills and was drafted over the period of a few weeks. It's here for posterity and as a diary entry. You may not learn anything from this post.

Ignorance is Bliss

What seems to continually disappoint me, despite knowing how ‘things are’, is tools and platforms are chosen before understanding of the tasks at hand is fully formed. Ever stop and ask yourself why?

I firmly believe it’s down to complexity depth perception and a misunderstanding of when ‘good enough’ is mistakenly just. The good enough aspects sometimes shape entire architectures and create huge stinking problems that would have never been there if the good enough was understood better.

Then there is the ‘tool-task paradox’; as in, one must learn to use some basic tools, so that one can develop skills at using tools. It’s possible however to use tools to mend a car, without having ever designed a car. Social media will have you believe a software engineer, developer and script writer are the same thing; it doesn’t take a genius to realise they are not. Practising software system architects typically know how to write scripts, but script writers do not know how to architect systems. An argument of whether people are capable of each stands.

With today’s society and a lack of wanting to learn from wizened industry veterans, I fear, such is the need to succeed, to have public wins (and ironically, blog about it), skill building is being stunted too early in the journey and history is just concreted over with ‘new learnings’.

How many cake makers, stick a professional price on their first cake? Can you imagine going to a surgeon who only ever played the game Operation? Doesn’t sit right does it? So why do we put up with such utter tosh in software? But David, that person went on a boot-camp for six months and is now an evangelist for a FAANG!

Ignorance is bliss so they say.

Three primary thoughts are contained in this diary style post.

The Joe Armstrong Take

Joe was a hero of mine. I never met him and it haunts me to this day I never did, but I watched his talks, read his Tweets and generally felt like I would have loved to chat in person. I’m not sure another fan boy would have been good for Joe though!

If you’ve never heard of this legend, Joe Armstrong was co-inventor of Erlang, a language of which its semantics and syntax broke my brain the first time I tried doing anything with it. Joe was an amazing communicator and he had a saying which lives on in my daily work:

“Make it work, make it beautiful”. — Joe Armstrong

Ideas are cheap and ten a penny as they say. I have notebooks scattered around the house that are full of them. I value the notebooks because they reflect a mental state, a time, a place or set of ideas when I was in some mental zone. Without execution, an idea is just a pleasant daydream and my notebooks are just crazy Dave thought history.

What Joe was on to is this (I believe); get something working, prove the idea out and almost irrelevant of the aesthetics. To understand a problem space, it must be explored and thoroughly. By exploring and be willing to just accept your first iteration is pure discovery, the understanding grows and initial thoughts change as to how, why and what to build. The output value of getting something working, is like no amount of creating PowerPoint decks. Unfortunately in business, most of the time, the PowerPoint deck leads the way, which can hamper the understanding that comes from problem space exploration. When you eventually build the $thing properly, you can apply design thinking and take care of lifecycle aspects, resulting in a system that can be maintained and not feared by the gods themselves.

In early exploration, I create many individual prototypes and iterate on them. The core of the system will be scaffolded out with function calls and over time, the system grows to be functional as print statements are replaced with library calls. Similar perhaps to how someone prepares to climbing a mountain. You don’t just whack on your backpack and tell your family you’ll see them in a few months.

We cannot know about the things we do not know ahead of time. To help here with exploration work, I create a set of guiding principles then retrospectively put the design together for the discovery process to see the big picture. Iteratively, it’s then possible to enhance and pontificate about improvements. The amount of times this process has lead to new thoughts or better ways is unreal.

If the idea is bad, you get to kill your baby before it takes over your life and demands free rent at 30 years old.

Joe changed my daily habits and I never got the chance to tell him so. Thank you Mr Armstrong.

John Carmack (Mr Doom)

First of all, thank you to Matthew Stone - @bigmstone for sharing this video with me. I’m fresh when it comes to computer graphics (although interested), but John’s energy and view of trying disprove ideas is great. In essence, this is the ‘antifragile’ principle. I also have to admit that I forgot John’s name and went back later to ask “Who the skinny clever dude was on that video?”. After being lambasted appropriately, Matt (eventually) jogged my memory. Weirdly, the contents I had remembered as a mental video; just not important details; like John’s name.

The idea is you should try to kill your ideas before they take hold and become something way bigger than something to pet, feed and love. Bad ideas need to die to free up brain cycles and prevent bad mental investments.

Do this early and be honest with yourself. Good ideas can be worked with, bad ideas can be stripped of the good parts and then locked in the cupboard of idea death.

The good news is, the exploration of even bad ideas will result in some new or refreshed knowledge you can carry forward. Such is the importance of exploration.

I’ve often struggled with brain queue depth and misplaced value issues. The freeing aspect of letting go of ideas is a real boost to mental fluidity. Once you employee these thoughts, it also becomes wonderfully hysterical when people are defensive over their $1b game changing idea. Execution is kind of all that matters. Organisations often play the patent game to prevent execution.

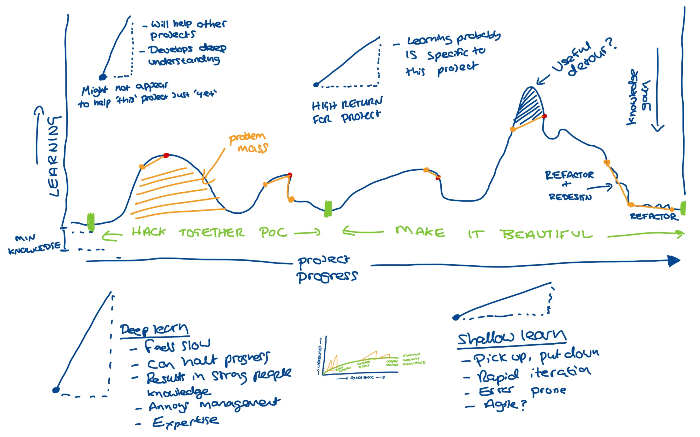

Vectorisation of Learning

Another mental illusion is time badly spent. Time at least in 2020, is a decreasing resource for humans. We all experience it at difference speeds and thus, it has different value depending on who we are, what we’re doing and what life situation we’re in. Given this view, when it comes to learning, we heavily target and constrain what we believe we need to learn in sacrifice of what we could learn.

As I’ve aged, inspiration has come in from so many angles and I no longer have fixed ideas on exploration. That said, I’m at a point in my career where I’ve been to enough tee shirt collecting camps, have received multiple wounds and as such, have enough foundational knowledge and knee jerk capability to identify foundational needs of a given problem space. What I’ve tried to do, is remove fixed ideas about ‘the right way’ to build something and more importantly, talk myself down from learning for the sake of it.

In networking, it’s all too easy to pick up a Cisco Press or Juniper book and crack on. In software, especially my passion being system control software, the learning is much more muddier. Without understanding the industry domain, the customer, their customers and needs, any attempt at fixed learning or development just ends in disappointment.

To help with this mental approach, I’ve come to think of learning as a vectorisation principle. Sometimes the difficulty of the material and breadth makes it feel like an uphill battle and when you take stock of forward motion for a project, it can feel like you’ve made no progress. As an opposite, you can also make huge amounts of progress when there is little to learn, hence the fixation I believe on ‘learning all the things’. Both are an illusion. Learning is a differential issue and momentum comes from starting coordinates in the domain space. Forward momentum might also be in the wrong direction, or the momentum may take you to the wrong place. If you haven’t explored the terrain, that’s likely to happen and the worst part is, you might not even know why you failed. You just did and that blows.

I firmly believe that by disproving ideas, exercising them rapidly and by keeping an open mind for learning and the outcomes of doing so, there is always a future to build interesting systems. The terrain of a project has many highs and lows and the most important thing I tell myself, they’re just guests that appear between point A and point B. I greet each of them with the same set of caution and acceptance. Each interaction adds understanding and pointers to missing information. What’s more, these pointers often have associated value because of the nature of the vector.

A project paradox (Dichotomy / Race Course paradox) that always makes me smile, is this: When travelling between A and B, once you get to the half way point, you do the next half way point and so on and so forth. You never actually complete the journey based on this paradox, but over time you get close. Software projects are mostly always the same; infrastructure without an end-state. The B coordinate continually changes too, adding to the fun.

Close

If anyone has read this, sorry, there are no golden nuggets here, just observations that I needed to scribble down and empty out of my grey matter.

As my view points become less sticky, I found a world of curiosity was at my finger tips, even at this point in my career. I would love to see a change in fixed thinking when it comes to network automation, but for now, I will remain in a somewhat cynical stoop and disappointed mental frame.

There is an ignition however in graph theory across the industry and for that, I’m super excited.

// Dave

- Tags: Software Skills, Learning Skills

- Categories: Learning Skills, Musings