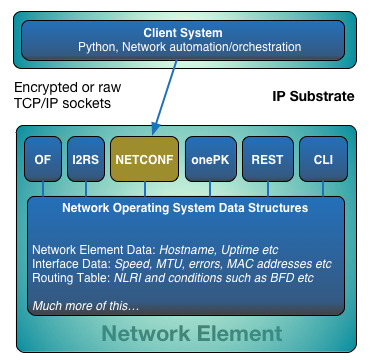

This is a self contained guide on how to use Juniper’s PyEZ library to connect to a Junos device and interact with it by NETCONF. As well as being a self contained guide, it’s also linked to from this article which provides an overview of Python programmability.

In order to provide a disciplined approach to utilising the framework provided by Jeremy Schulman’s talented team, please find a set of hypothetical requirements below.

It’s important to also establish some standards before writing code.

Methods = thisMethod()

Functions = thisFunction()

Variables = this_is_a_value = x

Class = ThisClass()

Fields = this_is_a_value = x

Private field = _private_field = x

Comment = # Comment blah blah stuff blah

Hypothetical Requirements: ACME Industries – NetOps requirements

ACME elevator music incorporated is seeing unprecedented growth for some unknown reason and have decided to do a health check on their network which currently consists of three devices, which includes a Juniper Firefly Perimeter (vSRX). You are to extract the information below and present it in a human readable format which can be entered in to a report. Please create re-usable code and scripts to add value to the network operations team.

- Hostname

- Model

- Uptime of each device

- Current software version

- Device serial number

- MAC address for each active Ethernet interface

Let’s begin

Let’s install PyEZ using the Python package manager called pip. Instructions on installation can be found on the PyEZ website.

pip install junos-eznc

Where do we go from here? Let’s just jump in knee deep and see if we can utilise the junos-eznc framework and connect to a device before we try anything else. A tenet of network engineering. Ping it before you break it. How would you know if it was working before you attempt to break it? I’ve fired up a Juniper Firefly VM (vSRX) on VMWare Fusion, it has an IP address of 172.16.49.136 and I’ve configured the username ‘dgee’ and password ‘Passw0rd’. Ensure that NETCONF is permitted inbound to the device with the config directly below. Look for the ‘netconf’ configuration statement. Also, ensure that firewall rules permit the traffic inbound on the interface that you’ll be accessing the Firefly instance on. In this case it’s ge–0/0/0.0, which is reachable via my Mac routing table.

dgee> show configuration security zones security-zone trust

<*snip*>

interfaces {

ge-0/0/0.0 {

host-inbound-traffic {

system-services {

netconf;

}

}

}

}

Now we’ve got the basics in place, let’s go right ahead and open the Python interpreter. Enter the code below. If you’re not totally familiar with the interpreter environment just yet, the ‘»>’ is akin to a prompt. Enter lines of code when this is present. You’ll notice when it’s not present, output from something (a function, class, or in our case device) resides. pprint is similar to print but is a bit more ‘prettier’.

Python 2.7.5 (default, Sep 12 2013, 21:33:34)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 5.0 (clang-500.0.68)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> # EXERCISE 1.0

>>> # You do not have to type this or the comment above as they are comments

>>>

>>> from pprint import pprint

>>> from jnpr.junos import Device

>>> dev1 = Device(host='172.16.49.136', user='dgee', password='Passw0rd')

>>> dev1.open()

Device(172.16.49.136)

>>> pprint( dev1.facts )

{'2RE': False,

'HOME': '/cf/var/home/dgee',

'RE0': {'last_reboot_reason': 'Router rebooted after a normal shutdown.',

'model': 'JUNOSV-FIREFLY RE',

'status': 'Testing',

'up_time': '18 minutes, 54 seconds'},

'domain': None,

'fqdn': 'Amnesiac',

'hostname': 'Amnesiac',

'ifd_style': 'CLASSIC',

'model': 'JUNOSV-FIREFLY',

'personality': 'SRX_BRANCH',

'serialnumber': 'ee9e0c8e09cd',

'srx_cluster': False,

'switch_style': 'VLAN',

'version': '12.1X44-D20.3',

'version_info': junos.version_info(major=(12, 1), type=X, minor=(44, 'D', 20), build=3),

'virtual': True}

>>> dev1.close()

First thoughts? If you didn’t get it right the first time either due to a typo or three, working so low down can become frustrating. How can we immediately move past this first new pain point? Before a solution is offered (and this is my solution, not necessarily correct for you), working this way is in parallel to working with the traditional CLI without the trusty question mark. Try entering the question mark and see what happens.

To ease the pain of repetitively typing all of our code and debugging any typos, let’s take change gear and enter our code in to a .py file and execute it via Python. We’ll also add some additional code which will allow us to interact with our environment interactively once all of the code has been executed. Below shows the additional code which achieves this. Comments have a # prepended in front of them. Important, for this exercise, although the comment instructs you to close the connection to the device and exit Python, please do NOT! The comments are there as good practise. We need the connection to be open for the remainder of our exercise up until writing production code!

# EXERCISE 1.1

from pprint import pprint

from jnpr.junos import Device

import code

dev1 = Device(host='172.16.49.136', user='dgee', password='Passw0rd')

dev1.open()

pprint( dev1.facts )

print "Welcome to the interactive shell"

code.interact(local=locals())

# Remember to close the connection before exiting from the interactive Python shell

# Execute the below:

# dev1.close()

# exit()

All of the information we require barring that related to interfaces is in our output from the Firefly VM. Try entering:

dir(dev1)

See what happens? We get a list of the functions that object dev1 has available. This is simple introspection, where we ask Python to look at itself and tell us what it sees in the object. Pretty neat huh?

Next, let’s extract the Ethernet MAC address information using the code below.

# EXERCISE 1.2

from jnpr.junos.op.ethport import EthPortTable

eths = EthPortTable(dev)

eths.get()

x = 0

while x < len(eths):

print "Interface: " + eths.keys()[x] + " Information"

print eths[x].items()

x += 1

For now, let’s not get too concerned with formatting the data. With any engineering, we want to make sure we have the right size nuts and bolts before we get the spanners out. Here’s a complete listing up to now of what we’ve covered with comments.

# EXCERCISE 1.3

# Code for 'CLI to Py' blog post by @davidjohngee

# Please adhere to Juniper's license terms and Jeremy's teams good will!

# This code imports required classes from PyEZ, pprint and our interactive code shell requirement so we can tinker.

from pprint import pprint

from jnpr.junos import Device

from jnpr.junos.op.ethport import EthPortTable

import code

# This is where we declare our run time global variables.

x = 0

# This is our 'main' code and entry point. We do this so code is reusable.

# For example, if we want to import any class or function we've defined in this file, but not execute

# any code that does something, then this facilitates that (if that makes sense?)

# Our __main__ code is executed if this file is executed first.

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Create our device object and assign the hostname or IP address, username and password

dev1 = Device(host='172.16.49.136', user='dgee', password='Passw0rd')

# Open a connection to the device. Please note, we're doing some very simple exception handling!

try:

dev1.open()

except:

print "Error Will Robinson, error"

# Print the element information

pprint( dev1.facts )

# Next up, let's create an object to store information pertaining to our Ethernet ports

eth_ports = EthPortTable(dev1)

# and obtain the information

eth_ports.get()

# Loop through the information using x as an index and print to stdout

while x < len(eth_ports):

print "Interface: " + eth_ports.keys()[x] + " Information"

print eth_ports[x].items()

x += 1

# Now dump in to the interactive shell

print "Welcome to the interactive shell"

code.interact(local=locals())

# Remember to close the connection before exiting from the interactive Python shell

# Execute the below:

# dev1.close()

# exit()

At this point, it will prove wise to assess what we’ve achieved and what we need to do in order to meet our requirements. As you’re no doubt experiencing, it’s easy to get lost in the actual code. The best way to stay focussed and on track is to…

Create a plan!

Here’s sanitised list of tasks that we need to achieve in order to meet our requirements:

- Create a client side data object to store our network element data in and provide functionality.

- Obtain the data via PyEZ.

- Normalise and store the data in our client side data object.

- Pretty print the data to complete and meet our original set of requirements.

So far we’ve done the fun bit, but that’s it. Good to play but not very useful.

Once we have the list, we can architect the requirements. We know that there will be data to store and we also know that some text manipulation will be required, which we can build in to a function. Let’s hit the list.

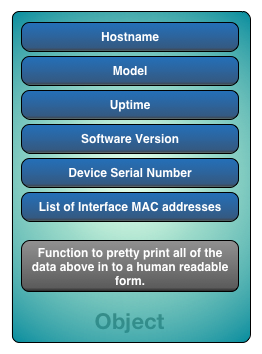

As is said, a picture says a thousand words. Here’s an image of our desired data object that we would like to use to store the network element data. A Python object can be used to store data, but it can also be used to house functions. A function typically does something to the data held within. In our case, we need a function to pretty print.

We also need to decide on a method of loading the data in to our object. We can do it at creation time via the class constructor, or we can create ‘setters’ to do it. I’m a fan of keeping things simple, so I’ve opted to populate the class via the constructor.

This class is simple, it loads the data and the __str__ function returns a pretty version when called. Obtaining the data was the hardest part. In order to access interface information, we need to create an EthPortTable object. We could create that in the __main__ section of our code, but that would mean an object accessing something in the global object space. To keep this tidy, let’s create the table within the class! The class constructor has the device class passed to it so the class constructor method can can call the EthPortTable.get() method, which in populates it. Notice that in the __str__ method, we index in to the EthPortTable via [x] and the ['macaddr'] index values. Check the output from exercise 1.3 to see where ['macaddr'] appears. This might seem a lot to take in. Look carefully how the code has developed from the ‘scratch pad’ version to a much tidier example at the bottom of the post. Check the PyEZ documentation for more info if you want more clarity on tables.

# EXERCISE 1.4

# Here a class is defined, which matches our requirements.

# 1. Uptime of each device

# 2. Current software version

# 3. Device serial number

# 4. MAC address for each Ethernet interface

class NetworkRequirements(object):

_hostname = ''

_model = ''

_uptime = ''

_version = ''

_serial = ''

_interfaces = []

def __init__(self, uptime, version, serial, hostname, model, device):

# This is our constructor. Populate each variable.

self._up_time = uptime

self._version = version

self._serial = serial

self._hostname = hostname

self._model = model

self._interfaces = EthPortTable(device)

self._interfaces.get()

def __str__(self):

# This is our special print function which returns a string (text) version of the object.

# We need to build our text up and structure it. We do this by appending the required text to a variable

# which we've called 'return_string'.

# n is a special sequence to insert a new line and t (can you guess?) is a tab.

# Once our string is complete, we 'return' it to the caller.

x = 0

return_string = ''

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += 16*" " + "Element Report"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Hostname: " + self._hostname

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Model: " + self._model

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Uptime: " + self._up_time

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Version: " + self._version

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Serial: " + self._serial

return_string += "n"

while x < len(self._interfaces):

return_string += "Interface " + self._interfaces.keys()[x] + "tMAC Address: " + self._interfaces[x]['macaddr'] + "n"

x += 1

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += 21*" " + "End of Element Report"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return return_string

Directly below is the output that meets our requirements. At the bottom of the post you will find two versions of code that provides the required output. Note that the code that allows you to enter interactive mode is still there. This allows you to play around and check objects etc after your code has executed. Handy for testing more functionality prior to building it! Finally, note that the interface list is built dynamically. We don’t know how many interfaces are present when we designed and built our class.

================================================================

Element Report

================================================================

Hostname: Amnesiac

Model: JUNOSV-FIREFLY

Uptime: 10 hours, 41 minutes, 35 seconds

Version: 12.1X44-D20.3

Serial: ee9e0c8e09cd

Interface ge-0/0/0 MAC Address: 00:0c:29:8e:09:cd

Interface ge-0/0/1 MAC Address: 00:0c:29:8e:09:d7

================================================================

End of Element Report

================================================================

Welcome to the interactive shell

Python 2.7.5 (default, Sep 12 2013, 21:33:34)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 5.0 (clang-500.0.68)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

(InteractiveConsole)

>>>

Here is version one of the code that uses all of the code from the exercises above.

# Code for 'CLI to Py' blog post by @davidjohngee

# Please adhere to Juniper's license terms and Jeremy's teams good will!

# This code imports required classes from PyEZ, pprint and our interactive code shell requirement so we can tinker.

from pprint import pprint

from jnpr.junos import Device

from jnpr.junos.op.ethport import EthPortTable

import code

# Here a class is defined, which matches our requirements.

# 1. Uptime of each device

# 2. Current software version

# 3. Device serial number

# 4. MAC address for each Ethernet interface

class NetworkRequirements(object):

_hostname = ''

_model = ''

_uptime = ''

_version = ''

_serial = ''

_interfaces = []

def __init__(self, uptime, version, serial, hostname, model, device):

# This is our constructor. Populate each variable.

self._up_time = uptime

self._version = version

self._serial = serial

self._hostname = hostname

self._model = model

self._interfaces = EthPortTable(device)

self._interfaces.get()

def __str__(self):

# This is our special print function which returns a string (text) version of the object.

# We need to build our text up and structure it. We do this by appending the required text to a variable

# which we've called 'return_string'.

# n is a special sequence to insert a new line and t (can you guess?) is a tab.

# Once our string is complete, we 'return' it to the caller.

x = 0

return_string = ''

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += 16*" " + "Element Report"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Hostname: " + self._hostname

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Model: " + self._model

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Uptime: " + self._up_time

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Version: " + self._version

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Serial: " + self._serial

return_string += "n"

while x < len(self._interfaces):

return_string += "Interface " + self._interfaces.keys()[x] + "tMAC Address: " + self._interfaces[x]['macaddr'] + "n"

x += 1

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += 21*" " + "End of Element Report"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return return_string

# This is our 'main' code and entry point. We do this so code is reusable.

# For example, if we want to import any class or function we've defined in this file, but not execute

# any code that does something, then this facilitates that (if that makes sense?)

# Our __main__ code is executed if this file is executed first.

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Create our device object and assign the hostname or IP address, username and password

dev1 = Device(host='172.16.49.136', user='dgee', password='Passw0rd')

# Open a connection to the device. Please note, we're doing some very simple exception handling!

try:

dev1.open()

except:

print "Error Will Robinson, error"

# Let's create our object and initialise it

vSRX01 = NetworkRequirements(dev1.facts['RE0']['up_time'], dev1.facts['version'], dev1.facts['serialnumber'], dev1.facts['hostname'], dev1.facts['model'], dev1)

# Now let's see if our class works and print out the data! Once we call this special class function, the string is returned as expected.

print vSRX01

# Now dump in to the interactive shell

print "nnWelcome to the interactive shell"

code.interact(local=locals())

# Remember to close the connection before exiting from the interactive Python shell

# Execute the below:

# dev1.close()

# exit()

This next version of the code provides an alternate method of structuring our class. As this article was written and reviewed, it was deemed that a more efficient method of iterating through the data in the EthPortTable exists. Whilst the value could be argued of placing both versions of code in this post, it clearly demonstrates a development and review cycle that exists in every project. There are always different and more efficient ways of writing something. The version below binds the EthPortTable to the dev1 object. This means that the dev1 device object can be passed around to different parts of the program. Every time a new table or set of data is bound to the device, it moves with it. Execute the code below and once you’re in the interactive Python shell, run dir(dev1) and notice how eth_ports is bound to our device object. Cool right?

# Code for 'CLI to Py' blog post by @davidjohngee

# Please adhere to Juniper's license terms and Jeremy's teams good will!

# This code imports required classes from PyEZ, pprint and our interactive code shell requirement so we can tinker.

from pprint import pprint

from jnpr.junos import Device

from jnpr.junos.op.ethport import EthPortTable

import code

# Here a class is defined, which matches our requirements.

# 1. Uptime of each device

# 2. Current software version

# 3. Device serial number

# 4. MAC address for each active Ethernet interface

class NetworkRequirements(object):

_hostname = ''

_model = ''

_uptime = ''

_version = ''

_serial = ''

_interfaces = []

_device = []

def __init__(self, uptime, version, serial, hostname, model, device):

# This is our constructor. Populate each variable.

self._up_time = uptime

self._version = version

self._serial = serial

self._hostname = hostname

self._model = model

self._device = device

# Here we bind an EthPortTable called 'eth_ports' to our device object field within the class.

self._device.bind(eth_ports = EthPortTable)

# Then we call '.get()' to populate the table.

self._device.eth_ports.get()

# The beauty of this now, is that we have bound a table to the dev1 itself and we can pass

# the same device to another function or class to do something else.

def __str__(self):

# This is our special print function which returns a string (text) version of the object.

# We need to build our text up and structure it. We do this by appending the required text to a variable

# which we've called 'return_string'.

# n is a special sequence to insert a new line and t (can you guess?) is a tab.

# Once our string is complete, we 'return' it to the caller.

x = 0

return_string = ''

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += 16*" " + "Element Report"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Hostname:tt" + self._hostname

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Model:ttt" + self._model

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Uptime:ttt" + self._up_time

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Version:tt" + self._version

return_string += "n"

return_string += "Serial:ttt" + self._serial

return_string += "n"

# As tables in PyEZ are iterable and since we've bound our table to our device, we can now do this.

for port in self._device.eth_ports:

return_string += "Interface " + port.name + "tMAC Address: " + port.macaddr + "n" # or you can do it like this: + port['macaddr'] + "n"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return_string += "n"

return_string += 21*" " + "End of Element Report"

return_string += "n"

return_string += 64*"="

return return_string

# This is our 'pyez_main' code and entry point. We do this so code is reusable.

# For example, if we want to import any class or function we've defined in this file, but not execute

# any code that does something, then this facilitates that (if that makes sense?)

# Our __main__ code is executed if this file is executed first.

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Create our device object and assign the hostname or IP address, username and password

dev1 = Device(host='172.16.49.136', user='dgee', password='Passw0rd')

# Open a connection to the device. Please note, we're doing some very simple exception handling!

try:

dev1.open()

except:

print "Error Will Robinson, error"

# Let's create our object and initialise it

vSRX01 = NetworkRequirements(dev1.facts['RE0']['up_time'], dev1.facts['version'], dev1.facts['serialnumber'], dev1.facts['hostname'], dev1.facts['model'], dev1)

# Now let's see if our class works and print out the data! Once we call this special class function, the string is returned as expected.

print vSRX01

# Now dump in to the interactive shell

print "nnWelcome to the interactive shell"

code.interact(local=locals())

# Remember to close the connection before exiting from the interactive Python shell

# Execute the below:

# dev1.close()

# exit()

I hope this has been informative and fun as it was to write. A special thank you shout out to Jeremy Schulman from Juniper Networks, who’s guidance is always invaluable.

Please feel free to comment whether it be positive or negative. All feedback is gratefully received and helps to improve the quality of future posts.