Objectifying the network using Python [Part One]

My last post was almost a rant more than anything of use, however that combined with Jeremy Schulman’s excellent post around network tooling should give an indication of where industry mindsets are the moment. Jeremy’s PyEZ library is great example of one network tool which allows the user to wield a powerful Python tool which effectively presents objects to empower the user to inspect and manipulate networking elements. Ok, under the hood it is the XML API, but it could be JSON or a RESTful API. In it’s most simplest form, it could be a HTTP GET request which fetches the data. Libraries such as PyEZ and it’s smarts, then parses, translates and objectifies the information. I’m pretty comfortable with this concept, but I thought it might be fun to exercise my Python foo and trigger some thinking.

I’ve built a set of Python classes which when coupled together (roughly), represents a model of a switch. Before we dive in to the code, I feel it wise to set some coding standards and naming conventions. The block below demonstrates the naming style I’ve gone with in the code for consistency.

Methods and functions, start with a lowercase letter, if it’s made up of two words, then use camel-back notation (i.e. capitalise the second word).

Fields and variables, use all lowercase words that are joined by under_scores (see what I did there?).

Classes, Capitalise each word forming the Class name.

Methods = thisMethod()

Functions = thisFunction()

Variables = this_is_a_value = x

Class = ThisClass()

Fields = this_is_a_value = x

Private field = _private_field = x

Comment = # Comment blah blah stuff blah

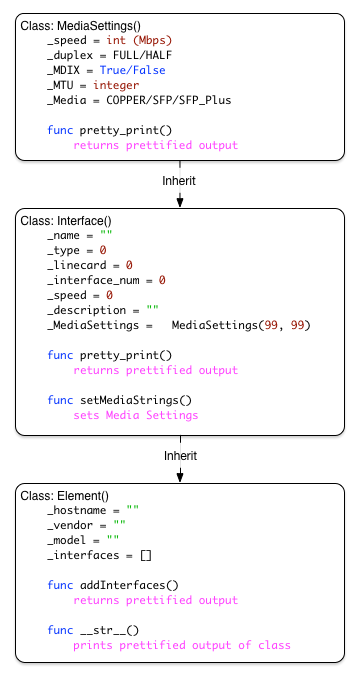

Before we go over our Python classes, let’s just go over a block diagram to illustrate the end game.

Now we’ve got that bit out out of the way, I’ll start by listing the all of the code that makes up each element of our model and I’ll explain block by block what each bit does.

# Interface type 'constants'

ETHERNET = 1

ATM = 2

# Interface Duplex 'constants'

FULL = 1

HALF = 2

# Interface Media 'constants'

COPPER = 1

SFP = 2

SFP_Plus = 3

class MediaSettings(object):

# Media Attributes

_speed = 0

_duplex = HALF

_MDIX = False

_MTU = 0

_Media = COPPER

def __init__(self, linecard, interface_num):

# This could be a southbound API call to a device. For now we'll hard code the values

self._speed = 1000

self._duplex = FULL

self._MDIX = True

self._MTU = 1514

self._Media = SFP_Plus

self._linecard = linecard

self._interface_num = interface_num

def __str__(self):

# We need to convert constants to strings...

# If this was C, C++ or TCL we could use a switch/case type system. Python is great for somethings, but not others.

duplex_string = ""

media_string = ""

# Let's do them in order, stating with Duplex

if self._duplex == HALF:

duplex_string = "HALF"

elif self._duplex == FULL:

duplex_string = "FULL"

# Now let's do Media

if self._Media == COPPER:

media_string = "COPPER"

elif self._Media == SFP:

media_string = "SFP"

elif self._Media == SFP_Plus:

media_string = "SFP+"

# Let's return the interface data!

return_string = "ntMedia Settings:nttSpeed: {0}nttDuplex: {1}nttAudo MDIX: {2}nttMTU: {3}nttMedia Type: {4}n" .format(self._speed, duplex_string, self._MDIX, self._MTU, media_string)

return return_string

class Interface(object):

# Interface attributes

_name = ""

_type = 0

_linecard = 0

_interface_num = 0

_speed = 0

_description = ""

_MediaSettings = MediaSettings(99, 99)

# Constructor for interface

def __init__(self, name, type, linecard, interface_num, description):

self._name = name

self._type = type

self._linecard = linecard

self._interface_num = interface_num

self._description = description

# Print to stdout class info

def __str__(self):

typeString = ""

# This could be a state machine. Keeping it simple for demonstration purposes.

if self._type == 1:

typeString = "Ethernet"

if self._type == 2:

typeString = "ATM"

return_string = ""

return_string += "Name: {0}ntDescription: {1}ntType: {2}ntLinecard: {3}ntInterface Number: {4}n".format(self._name, self._description, typeString, self._linecard, self._interface_num)

return_string += str(self._MediaSettings)

return return_string

# Get interface media settings

def setMediaSettings(self, temp_MediaSettings):

self._MediaSettings = temp_MediaSettings

class Element(object):

# Element attributes

_hostname = ""

_vendor = ""

_model = ""

_interfaces = []

# Element constructor

def __init__(self, hostname, vendor, model):

self._hostname = hostname

self._vendor = vendor

self._model = model

# Print Element info

def __str__(self):

# Return element information

return_string = ""

return_string = "-" *64 + "n"

return_string += "Element Informationn"

return_string += "-" *64 + "n"

return_string += "Hostname:t{0}nVendor:tt{1}nModel:tt{2}nn".format(str(self._hostname), str(self._vendor), str(self._model))

# Return interface info

return_string += "-" *32 + "n"

return_string += "Interface summaryn"

return_string += "-" *32 + "n"

# Loop through interfaces and print

for interface in self._interfaces:

return_string += str(interface)

return_string += "-" *64 + "n"

return return_string

# addInterfaces method to list

def addInterfaces(self, name, type, linecard, interface_num, description):

temp_InterfaceObj = Interface(name, type, linecard, interface_num, description)

# Retrieve media settings from Southbound Interface

temp_MediaSettings = MediaSettings(linecard, interface_num)

# Send media settings to Interface object

temp_InterfaceObj.setMediaSettings(temp_MediaSettings)

# Add interface to interface list

self._interfaces.append(temp_InterfaceObj)

Let’s start at the top of the code and work our way down. Python doesn’t handle constants as everything is a reference to an object, however I’ve used some constants the Python way to represent things that can only be in one of several states. These are interface types, interface duplex types and interface media types. If I set an interface to ‘ETHERNET”, the actual value it represents is then ‘1’.

# Interface type 'constants'

ETHERNET = 1

ATM = 2

# Interface Duplex 'constants'

FULL = 1

HALF = 2

# Interface Media 'constants'

COPPER = 1

SFP = 2

SFP_Plus = 3

Next up is the MediaSettings class. This class contains settings which are speed, duplex, MDIX, MTU and Media. This class could contain a southbound call to hardware to obtain these settings, but for ease I’ve hardcoded the settings in the constructor (__init__). The only complex piece here is the __str__(self) function. In a CLI when you hit something like “show interface x/x” in Cisco’s IOS for example, you expect human readable output. This method in a class when called presents prettified output.

class MediaSettings(object):

# Media Attributes

_speed = 0

_duplex = HALF

_MDIX = False

_MTU = 0

_Media = COPPER

def __init__(self, linecard, interface_num):

# This could be a southbound API call to a device. For now we'll hard code the values

self._speed = 1000

self._duplex = FULL

self._MDIX = True

self._MTU = 1514

self._Media = SFP_Plus

self._linecard = linecard

self._interface_num = interface_num

def __str__(self):

# We need to convert constants to strings...

# If this was C, C++ or TCL we could use a switch/case type system. Python is great for somethings, but not others.

duplex_string = ""

media_string = ""

# Let's do them in order, stating with Duplex

if self._duplex == HALF:

duplex_string = "HALF"

elif self._duplex == FULL:

duplex_string = "FULL"

# Now let's do Media

if self._Media == COPPER:

media_string = "COPPER"

elif self._Media == SFP:

media_string = "SFP"

elif self._Media == SFP_Plus:

media_string = "SFP+"

# Let's return the interface data!

return_string = "ntMedia Settings:nttSpeed: {0}nttDuplex: {1}nttAudo MDIX: {2}nttMTU: {3}nttMedia Type: {4}n" .format(self._speed, duplex_string, self._MDIX, self._MTU, media_string)

return return_string

The next class to talk about is the Interface class. This class presents settings: name, type, linecard, interface_num, speed, description and MediaSettings which is an instantiation of the class we just covered off. Please note, I’ve used (99, 99) as constructor defaults, as it’s unlikely that our switch will have 99 line cards 🙂 Again, we have a __str__(self) method as well as a setMediaSettings method which ‘retrieves’ the media settings for the specific interface from the ‘southbound API’. As we’ve already discussed, in this example, the media settings are hardcoded for ease. Settings include: name, type, linecard, interface_num, speed, description and MediaSettings.

class Interface(object):

# Interface attributes

_name = ""

_type = 0

_linecard = 0

_interface_num = 0

_speed = 0

_description = ""

_MediaSettings = MediaSettings(99, 99)

# Constructor for interface

def __init__(self, name, type, linecard, interface_num, description):

self._name = name

self._type = type

self._linecard = linecard

self._interface_num = interface_num

self._description = description

# Print to stdout class info

def __str__(self):

typeString = ""

# This could be a state machine. Keeping it simple for demonstration purposes.

if self._type == 1:

typeString = "Ethernet"

if self._type == 2:

typeString = "ATM"

return_string = ""

return_string += "Name: {0}ntDescription: {1}ntType: {2}ntLinecard: {3}ntInterface Number: {4}n".format(self._name, self._description, typeString, self._linecard, self._interface_num)

return_string += str(self._MediaSettings)

return return_string

# Get interface media settings

def setMediaSettings(self, temp_MediaSettings):

self._MediaSettings = temp_MediaSettings

The last component to look at is the Element class. The element class has fields: hostname, vendor, model and interfaces list as you’d expect a rubbish model of a switch to have! As per the other classes, it contains the __str__(self) method, but it also includes an addInterfaces() method which takes a number of parameters which are: name, type, linecard, interface_num and description.

class Element(object):

# Element attributes

_hostname = ""

_vendor = ""

_model = ""

_interfaces = []

# Element constructor

def __init__(self, hostname, vendor, model):

self._hostname = hostname

self._vendor = vendor

self._model = model

# Print Element info

def __str__(self):

# Return element information

return_string = ""

return_string = "-" *64 + "n"

return_string += "Element Informationn"

return_string += "-" *64 + "n"

return_string += "Hostname:t{0}nVendor:tt{1}nModel:tt{2}nn".format(str(self._hostname), str(self._vendor), str(self._model))

# Return interface info

return_string += "-" *32 + "n"

return_string += "Interface summaryn"

return_string += "-" *32 + "n"

# Loop through interfaces and print

for interface in self._interfaces:

return_string += str(interface)

return_string += "-" *64 + "n"

return return_string

# addInterfaces method to list

def addInterfaces(self, name, type, linecard, interface_num, description):

temp_InterfaceObj = Interface(name, type, linecard, interface_num, description)

# Retrieve media settings from Southbound Interface

temp_MediaSettings = MediaSettings(linecard, interface_num)

# Send media settings to Interface object

temp_InterfaceObj.setMediaSettings(temp_MediaSettings)

# Add interface to interface list

self._interfaces.append(temp_InterfaceObj)

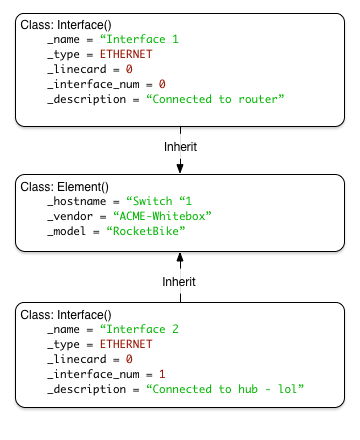

All of this code is pretty unspectacular. It does nothing more than populate fields with values that represent components of a very simple switch. We’ve not even got a model yet! So, let’s build a model.

Ok, so now we have our model, we can actually write the code to build our model and see what pretty output it gives us. First we import out set of Classes from the Python file. Then we instantiate a Class called Whitebox_Switch which is an Element Class. Once have that object created, we add a couple of interfaces and pass some parameters to construct them. Finally we generate the pretty print output we so desire.

from ElementPackage import element_components_2

from ElementPackage.element_components_2 import *

# Create an element called 'Whitebox_Switch'

Whitebox_Switch = Element("Switch 1", "ACME-Whitebox", "RocketBike")

# Add an interface to Whitebox_Switch called 'Interface 1' and set it to type Ethernet, line card 0, port 0 and set the description as "connected to router".

Whitebox_Switch.addInterfaces("Interface 1", ETHERNET, 0, 0, "Connected to router")

# Add an interface to Whitebox_Switch called 'Interface 2' and set it to type Ethernet, line card 0, port 1 and set the description as "connected to a hub - lol".

Whitebox_Switch.addInterfaces("Interface 2", ETHERNET, 0, 1, "Connected to hub - lol")

# Do some pretty print output

print Whitebox_Switch

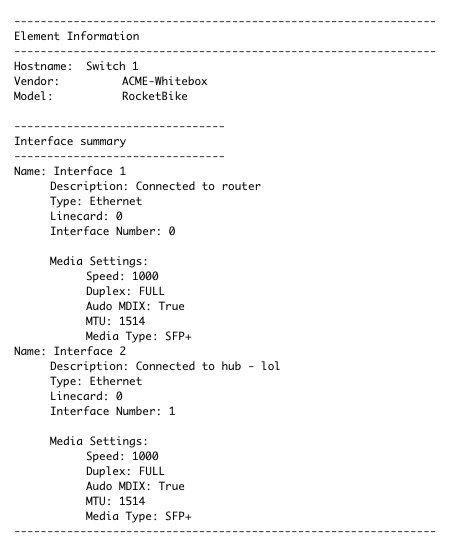

Here’s the prettified output we’re kind of familiar with.

Sorry about the typos

So what’s the point?

As the header above alludes to, what’s the point of this? Well, a lot of ‘controller’ technology for SDN and network automation solutions rely on getting and parsing information out of network elements, and painfully in a lot of cases. Some systems use CLI and screen scraping to obtain the information. Imagine receiving the information above and having to take the bits you want out of it, or create classes which represent the information. The PyEZ library and Cisco’s onePK allow the end user to get the information programmatically without messing around ripping information out of pretty CLI dumps. What’s more, they also allow you to manipulate and change the data too. It’s easy to see why the world is going mad for these kinds of tools when you realise you can access information in the language of your choice.

Before I say goodbye for now, I want to cover off one last thing. Say you want to change a hostname programmatically but you’re having to do it via CLI scraping and posting CLI commands which are wrapped up in your own classes, wouldn’t it be easier to just do something like the below? Using the code examples that we’ve already covered off, this is how you’d do it. In the real world, you might have to form a message to send to the network element, but it isn’t that different otherwise!!!

Whitebox_Switch._hostname = "Switch 2"

Isn’t that easier? Now imagine giving the power to an application to change network parameters. Scary thought huh?

// Dave

- Tags:

- Categories: